A deadly pall hung over the frightened villagers, and all those weary eyes followed the dying man as he was led bound to the gallows. Wearied eyes, tired spheres, they had seen such evil all their life, but never in such stark, such outright—never in the light.

They all knew their judge was corrupt—how many of them had been driven to the necessity of offering him what bribes they could scrounge up just to come before his bench?—but ever before this he had worn a respectable mask of friendly demeanor. Not now. It had dropped. He had nearly writhed during the trial, and his face had transformed into a monstrous snarl.

The prisoner ascended the rough, plank steps; his bruised and purple face turned upward toward heaven, his swollen eyes searching the clear, blue sky.

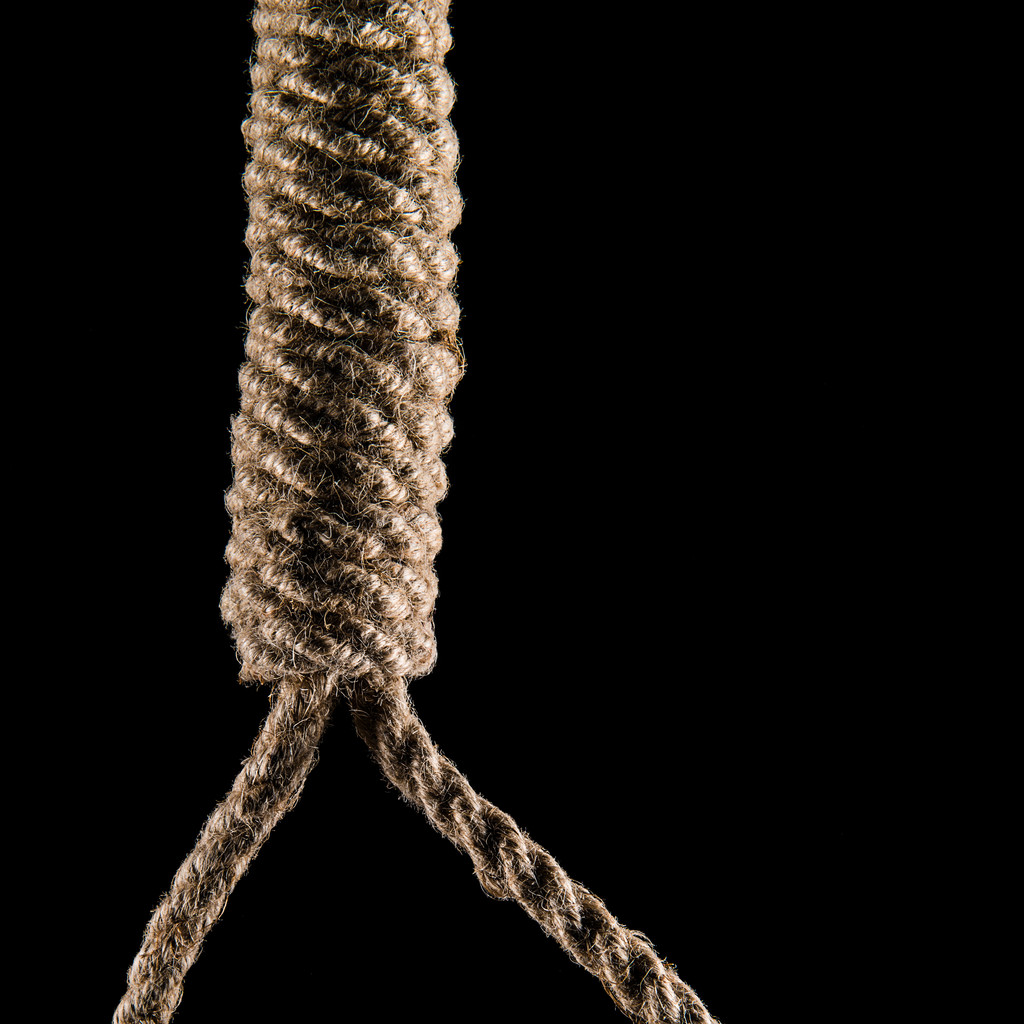

As they stood him over the trapdoor and tightened the cord around his neck, an official began to read off the crimes, a distorted account of his last few years embellished here and there by the wholesale invention of his enemies.

The executioner’s hand was to the leaver when a voice suddenly broke out:

“Stop!”

The parson, that mild man of quiet erudition—cousin to the judge—his voice had never squealed in such desperate a cry.

He fought his way through the stunned crowd which slowly gave to him. Up those same splintered planks the condemned had walked, the parson marched, and beside the condemned he stood. The crowd could not hear what he said to the hooded killer, but the hand receded.

The parson came to the condemned and whispered with him. The people watched their holy man make the sign of the cross over the dying man.

The parson turned to the people.

“This is a different pulpit,” he began, “than where you see me, yes?” Outside the cathedral, there was no echo to carry his weak voice. He watched the people coming nearer, crowding near the gallows.

With a swallow, he made himself shout, tearing at his throat:

“I do not speak from this pulpit often! Perhaps I should. Perhaps I will be brought back here myself. You know why this man is here. It is nothing to do with these calumnies and lies we’ve heard. He’s here because you hear him! You never heard me. Church is a place of habit with you. You walk there in your sleep. But you heard this man. You changed.” Panting, the parson looked from side to side. “And where are his accusers? Where are those men but counting their money in the dark? Our Honorable judge nearly handed over those thirty pieces of silver in front of us when he corrected their testimony in the dock. They hadn’t learned their lies well enough!”

“Get back to your church,” snarled the official. “This is no concern of yours.”

“And how will you escape the wrath of God when this man’s blood calls out? Will you not be marked forever a murderer?”

The official snapped his fingers, and pointed to the parson. His two guards left his side, and clambered with all their armor up the rough steps.

“This is wrong!” the parson shouted as a benediction as he was dragged away, his shrill voice, unused to shouting, breaking.

The official snapped his fingers and pointed to the hooded man, but the executioner did not move.

With a turned lip, the official shouted, “Do your duty!”

But the nameless man would not set his hand upon that lever again.

With an exasperated sigh, the official stomped toward the gallows, stomped up the steps, stomped over to the executioner, shoving him aside, and taking the leaver in both hands, did the wicked deed.